After three years of construction, a “worldwide unique” hydraulic engineering laboratory of BOKU Vienna was opened last summer in Vienna-Brigittenau directly on the Danube. The special thing about it is that processes in rivers can be researched here on an original scale. Initial test runs promise far-reaching findings.

The focus is on flood protection, ecology, hydropower, navigation and all processes that take place in rivers under the influence of climate change. The water is taken directly from the Danube by opening a barrage, it flows through the huge hall of the new building directly behind the Nussdorf weir like a small river and is discharged into the Danube Canal at the other end, explains Helmut Habersack, initiator and Scientific Director of the Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) Vienna.

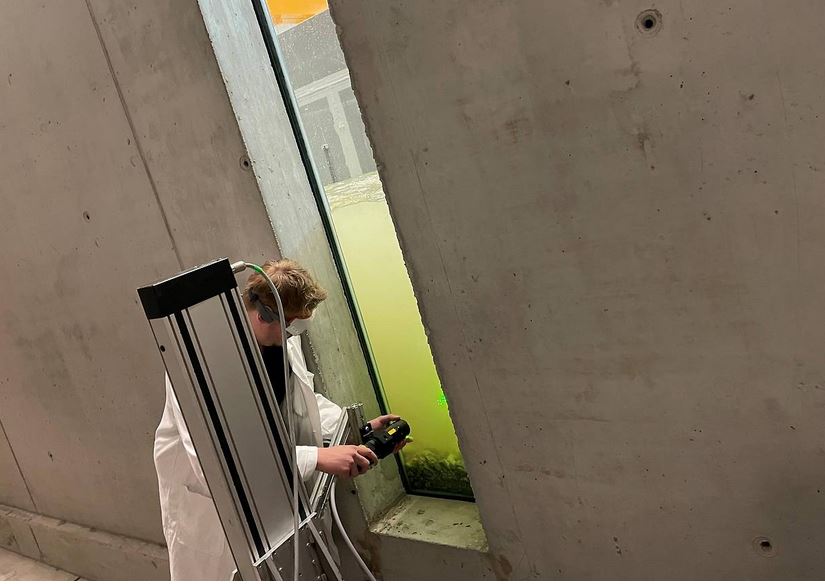

Eva Manhart | APA

There are two differently sized channels in the hall, which are flexible in size. The large channel can be extended to a total length of 90 metres and a width of 25 metres using flexible modules and walls. The maximum water depth is 3.50 metres.

Unique in the world

“The globally unique thing is that we can channel up to 10,000 litres per second through the hall by simply opening the gates,” says Habersack. The difference in water level between the Danube and the Danube Canal of three metres means that no pumps are required. “This is unrivalled anywhere else in the world, and we are therefore able to carry out one-to-one tests here,” says Habersack in the “Wien heute” interview.

As this was the case with smaller model experiments in the old BOKU water laboratory, scaling is hardly necessary any more, enthuses Habersack: “We no longer need to scale down the stones or other elements such as trees or fish. In the past, this often did not correspond to nature in terms of size.”

Christoph Gruber | BOKU-IT

Theory and practice diverge

When taking water from the Danube, a screen holds back fish from the river; if smaller fish still get through, they simply swim through the hall and out again. In the hall, natural phenomena such as river bed erosion, silting, flooding, drying out, ecological processes and the interaction between river and groundwater can be researched under laboratory conditions in two differently sized channels, in addition to other experiments.

According to Habersack, the test operation that has been running since January has already shown that some processes – as assumed – run differently than in earlier, smaller model tests. And even old calculations are not always correct: “We have already seen that old formula approaches do not always match reality. It probably has to do with the fluctuation in flow velocity and the formation of vortices that occur.” According to the hydraulic engineering expert, computers also often continue to work with the old formulas. This could change.

“The Danube has a completely disturbed sediment balance”

A hydropower turbine is also available for experiments. However, a major focus is the disturbed sediment balance of rivers and the Danube in particular: “The Danube has a completely disturbed sediment balance.” Sediments are sand and stones that are transported in the river. And this sediment in the Danube apparently “no longer reaches Vienna because it is already retained up in the mountains and rivers,” explains Habersack.

“So you then have the problem that the Danube digs itself in. And when it burrows in, the water level sinks, even in the national park.” This could then lead to the national park drying out, “and we want to ensure that this sediment continuum is restored”.

Doris Manola | ORF Wien

The research results can also be used to draw conclusions for shipping, hydropower plant construction and the planned partial restoration of the Danube. The EU project “DANUBE4all”, coordinated by Habersack and with a budget of 8.5 million euros, began in January 2023, will run for five years and aims to develop a Danube restoration action plan with the involvement of the population for the first time, says Habersack. New power plants, for example, must now be built in such a way that they can channel sediment through.

According to Habersack, the Danube delta, for example, receives 60 per cent less suspended matter per year due to sediment deposits in the reservoirs of power plants and other transverse structures: The result is coastal and sandy beach erosion.

In addition to research, exhibitions in the Public Lab are also planned for the upper floor of the new hydraulic engineering laboratory – especially for school classes, teachers and, of course, anyone interested in the Danube, hydraulic engineering and water research.

Location: Am Brigittenauer Sporn 3, 1200 Vienna | https://boku.ac.at/wau/iwa